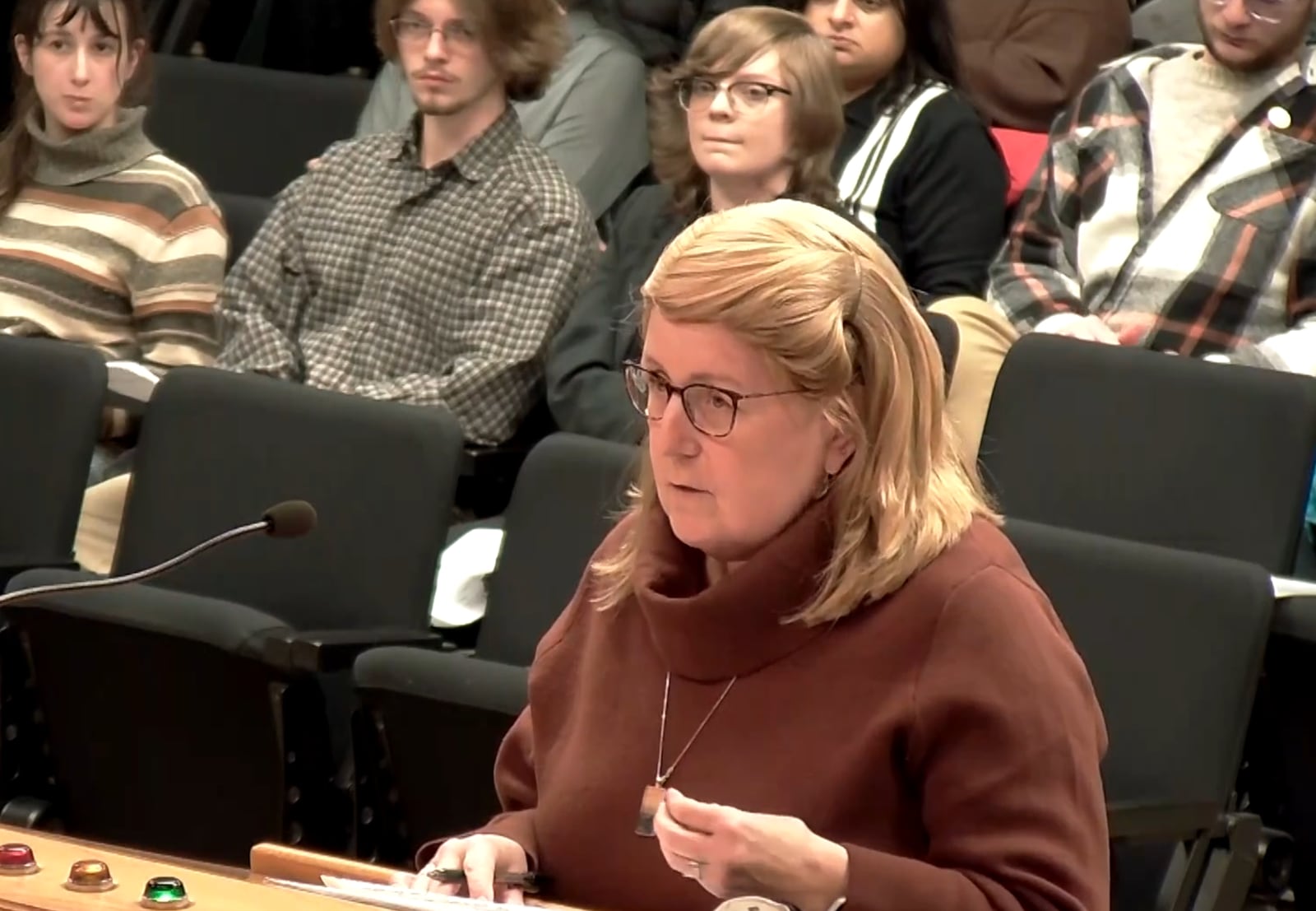

Joyce Probst MacAlpine at a recent meeting asked commissioners to ensure that data isn’t being used to target vulnerable neighbors, like immigrants and others.

“There’s a concern that somehow the restrictions in the contract that you have could be worked around, maybe through the work of a task force, revisions to the hot list, or some other loophole they can find to sell more data to their customers,” she said.

Flock cameras are mounted to poles and capture a still image of a vehicle license plate number — these photos go to a cloud storage system. And the cameras can send real-time alerts if the plate number belongs to a stolen vehicle or one being sought by law enforcement because of an AMBER alert or other missing person alert.

The American Civil Liberties Union has raised concerns about Flock cameras being used by the federal government for immigration enforcement and other operations.

“The tech news outlet 404Media obtained records of nationwide searches (of Flock data) which include a field in which officers list the purpose of their search,” according to a 2025 ACLU newsletter. “These records revealed that many of the searches were carried out by local officers on behalf of ICE for immigration purposes, including its notorious Enforcement and Removal Operations division.”

Melissa Bertolo, formerly the program director for Welcome Dayton, told Dayton commissioners that she’s concerned with data security. She called automatic license plate readers “one of the most pervasive surveillance tools used by federal immigration enforcement agencies.”

“It’s used to survey and ultimately detain the most vulnerable members of our communities, and we have the power through our procurement to turn off these surveillance cameras and protect our residents’ safety and privacy,” she said.

Dayton Police Chief Kamran Afzal and Maj. Jason Hall told commissioners and concerned residents that the city’s contract with Flock contains provisions against searches made for certain reasons: immigration and reproductive rights are prohibited reasons.

Images and data obtained through the cameras, unless the information is being used as a part of a criminal investigation, are deleted every 30 days. Automated license plate reader data is also exempt from Ohio public records law, Hall and Afzal said.

“We share our data with local law enforcement in Ohio. We will not share with any federal agencies. That’s written in the contract, and that’s how we manage it,” Afzal said. “I can tell you that immigration is the furthest thing from our mind about what we are doing, our service for the community.”

City officials also said Dayton police worked with neighborhoods, creating and developing safety plans. Public meetings about public safety and the Flock cameras were held from August to October.

Several residents also asked if the city’s own policies should have required a public hearing and an impact report for the increase in the number of cameras used. City officials said the expansion complies with the surveillance ordinance because the technology was approved in 2023.

Commissioner Darryl Fairchild, who said he previously voted against the camera contract, said he felt the “environment” is different now than it was in 2023. He said reports of “hacked” data are concerning.

Commissioner Chris Shaw said the Flock cameras have been a “community conversation,” and neighborhood associations played a crucial role in where they were installed. But Shaw said the commission should continue to evaluate the program — “like with any policy implementation we put forward.”

“There has been a community effort, all along, to kind of address these issues and ensure the safety of our citizens, which we feel most importantly about in terms of our vulnerable citizens,” he said.

About the Author